Article ARTisSpectrum – Life with the Wayana Amerindians

I f you follow the news, even for just a day, you won’t be able to avoid noticing the broad range of issues related to injustice. Every day, there are silent tragedies taking place all around the world, which we do not hear about unless we are being directly exposed or affected. Certain events affect me so deeply that I feel obliged to stop whatever I am doing and reassess my priorities. Witnessing a catastrophe involving an entire population arouses my compassion and compels me to take action on the matter.

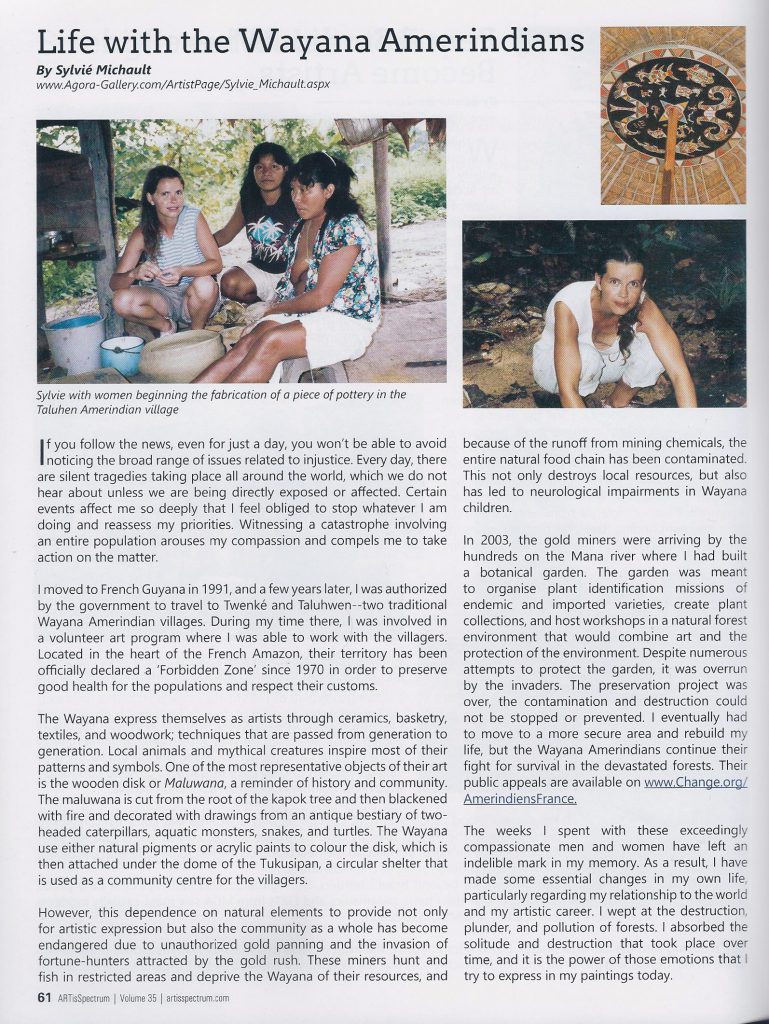

I moved to French Guyana in 1991, and a few years later, I was authorized by the government to travel to Twenke and Taluhwen–two traditional Wayana Amerindian villages. During my time there, I was involved in a volunteer art program where I was able to work with the villagers. Located in the heart of the French Amazon, their territory has been officially declared a ‘Forbidden Zone’ since 1970 in order to preserve good health for the populations and respect their customs.

The Wayana express themselves as artists through ceramics, basketry, textiles, and woodwork; techniques that are passed from generation to generation. Local animals and mythical creatures inspire most of their patterns and symbols. One of the most representative objects of their art is the wooden disk or Matuwana, a reminder of history and community. The maluwana is cut from the root of the kapok tree and then blackened with fire and decorated with drawings from an antique bestiary of two-headed caterpillars, aquatic monsters, snakes, and turtles. The Wayana use either natural pigments or acrylic paints to colour the disk, which is then attached under the dome of the Tukusipan, a circular shelter that is used as a community centre for the villagers.

However, this dependence on natural elements to provide not only for artistic expression but also the community as a whole has become endangered due to unauthorized gold panning and the invasion of fortune-hunters attracted by the gold rush. These miners hunt and fish in restricted areas and deprive the Wayana of their resources because of the runoff from mining chemicals, the entire natural food chain has been contaminated. This not only destroys local resources, but also has led to neurological impairments in Wayana children.

In 2003, the gold miners were arriving by the hundreds on the Mana river where I had built a botanical garden. The garden was meant to organise plant identification missions of endemic and imported varieties, create plant collections, and host workshops in a natural forest environment that would combine art and the protection of the environment. Despite numerous attempts to protect the garden, it was overrun by the invaders. The preservation project was over, the contamination and destruction could not be stopped or prevented. I eventually had to move to a more secure area and rebuild my life, but the Wayana Amerindians continue their fight for survival in the devastated forests. Their public appeals are available on www.Change.org/ AmerindiensFrance.

The weeks I spent with these exceedingly compassionate men and women have left an indelible mark in my memory. As a result, I have made some essential changes in my own life particularly regarding my relationship to the world and my artistic career. I wept at the destruction, plunder, and pollution of forests. I absorbed the solitude and destruction that took place over time, and it is the power of those emotions that I try to express in my paintings today.

I moved to French Guyana in 1991, and a few years later, I was authorized by the government to travel to Twenke and Taluhwen–two traditional Wayana Amerindian villages. During my time there, I was involved in a volunteer art program where I was able to work with the villagers. Located in the heart of the French Amazon, their territory has been officially declared a ‘Forbidden Zone’ since 1970 in order to preserve good health for the populations and respect their customs.

The Wayana express themselves as artists through ceramics, basketry, textiles, and woodwork; techniques that are passed from generation to generation. Local animals and mythical creatures inspire most of their patterns and symbols. One of the most representative objects of their art is the wooden disk or Matuwana, a reminder of history and community. The maluwana is cut from the root of the kapok tree and then blackened with fire and decorated with drawings from an antique bestiary of two-headed caterpillars, aquatic monsters, snakes, and turtles. The Wayana use either natural pigments or acrylic paints to colour the disk, which is then attached under the dome of the Tukusipan, a circular shelter that is used as a community centre for the villagers.

However, this dependence on natural elements to provide not only for artistic expression but also the community as a whole has become endangered due to unauthorized gold panning and the invasion of fortune-hunters attracted by the gold rush. These miners hunt and fish in restricted areas and deprive the Wayana of their resources because of the runoff from mining chemicals, the entire natural food chain has been contaminated. This not only destroys local resources, but also has led to neurological impairments in Wayana children.

In 2003, the gold miners were arriving by the hundreds on the Mana river where I had built a botanical garden. The garden was meant to organise plant identification missions of endemic and imported varieties, create plant collections, and host workshops in a natural forest environment that would combine art and the protection of the environment. Despite numerous attempts to protect the garden, it was overrun by the invaders. The preservation project was over, the contamination and destruction could not be stopped or prevented. I eventually had to move to a more secure area and rebuild my life, but the Wayana Amerindians continue their fight for survival in the devastated forests. Their public appeals are available on www.Change.org/ AmerindiensFrance.

The weeks I spent with these exceedingly compassionate men and women have left an indelible mark in my memory. As a result, I have made some essential changes in my own life particularly regarding my relationship to the world and my artistic career. I wept at the destruction, plunder, and pollution of forests. I absorbed the solitude and destruction that took place over time, and it is the power of those emotions that I try to express in my paintings today.

Sylvie Michault – March 2016