Thin skinned

In the preface of “The unique brush stroke”, a monograph dedicated to the callygraphy artist Fabienne Vernier, the moment preceding the act of creation is described as follows: “To absorb oneself, to become motionless and silent and stupid like a tree stump, to make your heart minuscule and attentive, receptive to the tiniest marvels, to stay in tune with the universe, and to perceive it certainly with one’s eyes, but above all with one’s soul, while within oneself, ineffably, mysteries are transmuting”. I could make mine this quotation.

For long I have wondered if the learning of photographical technique, instead of facilitating the mastery of cameras’ manipulation, would not deprive me of my freedom to invent, to grope around, to try out compositions without taking into account what was possible or not to obtain, without anticipating the result.

I love above all the irrational pleasure that overwhelms me at the thought that this almost mysterious object, made available by decades of technological research, will allow me, at the end of thrilling hours, to perceive the splendors of

a universe barely visible to the naked eye.

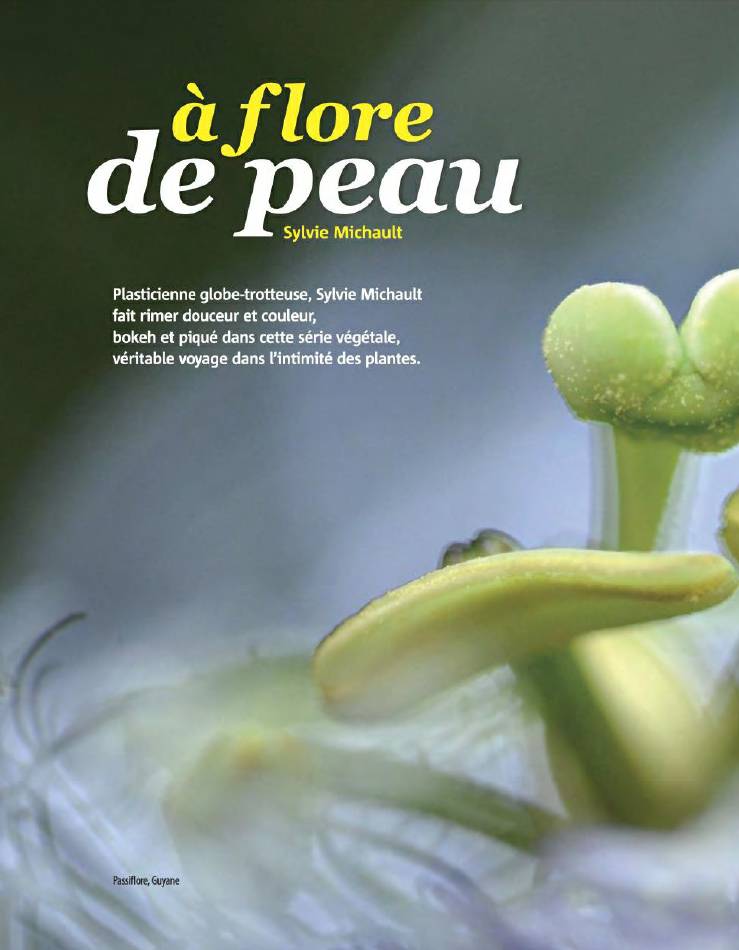

As the safety of persons and property can become problematical in French Guyana, photographing discreetly or in very isolated places is often the best way to avoid covetousness.

Certainly, the coastal gardens are overflowing with tropical varieties, each more luxuriant than the last. But to walk silently in the Amazonian forest, made dizzy by the humming and the chattering of the fauna at the crack of dawn, to go along the coves’ black shimmering waters and be enraptured by the incredible inventiveness of the plant kingdom in its

most primary state is an unequalled pleasure, one of these precious presents whose memory remains untouched for a lifetime.

Ten years spent in the heart of the rainforest on the banks of the Mana river, far from any villages, any means of communication, without electricity nor running water, without walls, nor windows, leave significant marks, sometimes

out of sync to the eyes of a western world where it often comes to matters of performance and competitiveness.

Without any other kind of support than a few scarce specialized magazines found in Guyana’s small towns’ points of sale, the learning process of macrophotography technique turned out to be more uncertain than I had foreseen, to such

an extent that the best part of my photos was at first realized in a so to speak… intuitive mode. But over time and at the cost of a little discipline, the complex universe of plants macrophotography offered me not only beautiful surprises but also lines of thinking that led me beyond the contemplation of a perfect shape.

I do not attempt to reproduce reality – so many photographers do it so well! – but when a wild flower, a blade of grass or a piece of bark, humble and tiny within the landscape, attracts me, it becomes the secret passageway that take me between the mirror of appearances and the soft uncertainties of my imagination.

Flower, leaf or tree, I do not always know your name, I have never studied you at university nor in books, I know almost nothing of your fragile existence, of the prowesses you have achieved to overcome ordeals. But here you are, for an hour, a summer, a century, welcoming kindly the passersby’s look.

Grass or poppy of one day, frail splinter of wood wound in the folds of a root, you give me the invaluable, the perpetual renewal of my sensitive faculties of which some, maybe the most powerful ones, slip out of all attempt of writing. You distill under my skin the shivers of a moment, you invite me to wonderment and nourish one of the indispensable qualities to our human nature: inspiration.

Needless to say, watching closer, not everything in nature offers the same esthetic value. A tangle of brambles on a muddy ground does not captivate the look as might a colorful meadow sparkling in a spring morning light. And yet, we

often go blindly past dispersed treasures by the side of a path or over a bank, whatever the season. The most improbable stroll becomes then a paper chase that sharpens our senses. Somewhere, a micro-picture awaits us that will combine light, spaces, lines and textures as soon as a forgotten leaf elegantly basks in a pretty back light, revealing us the shaded

palette of its transparence.

Even though the shooting conditions differ from one continent to the other, all the photographs in this portfolio were

taken hand-held. Sylvie has left aside the Nikon D90 and the Tamron 90mm macro lens of her beginnings for a D7100 coupled to the AF-S Micro Nikkor 60mm f/2,8 G and a 24mm extension ring: wide apertures for shallow depths of field and all senses awakened!

A weaver in a first life, Sylvie sets up her workshop by the ocean in Quiberon while teaching part of the year the diversity of weaving and vegetal dyeing techniques at the gates of the Vallée des Merveilles in the Mercantour. She keeps up studying in the South of France, becomes textile sculptress, then visual artist, and eventually embarks with her

children on a sailboat toward South America. After living in Brazil and in the Caribbean, she settles in French Guyana, where she teaches graphic arts and presents numerous vegetal art exhibitions.